The Milgram experiments: Findings on obedience

The 1960s Milgram experiments are well-known, but not often thoroughly explored. Milgram did 18 variations of his famous shock generator tests, and the details are worth knowing.

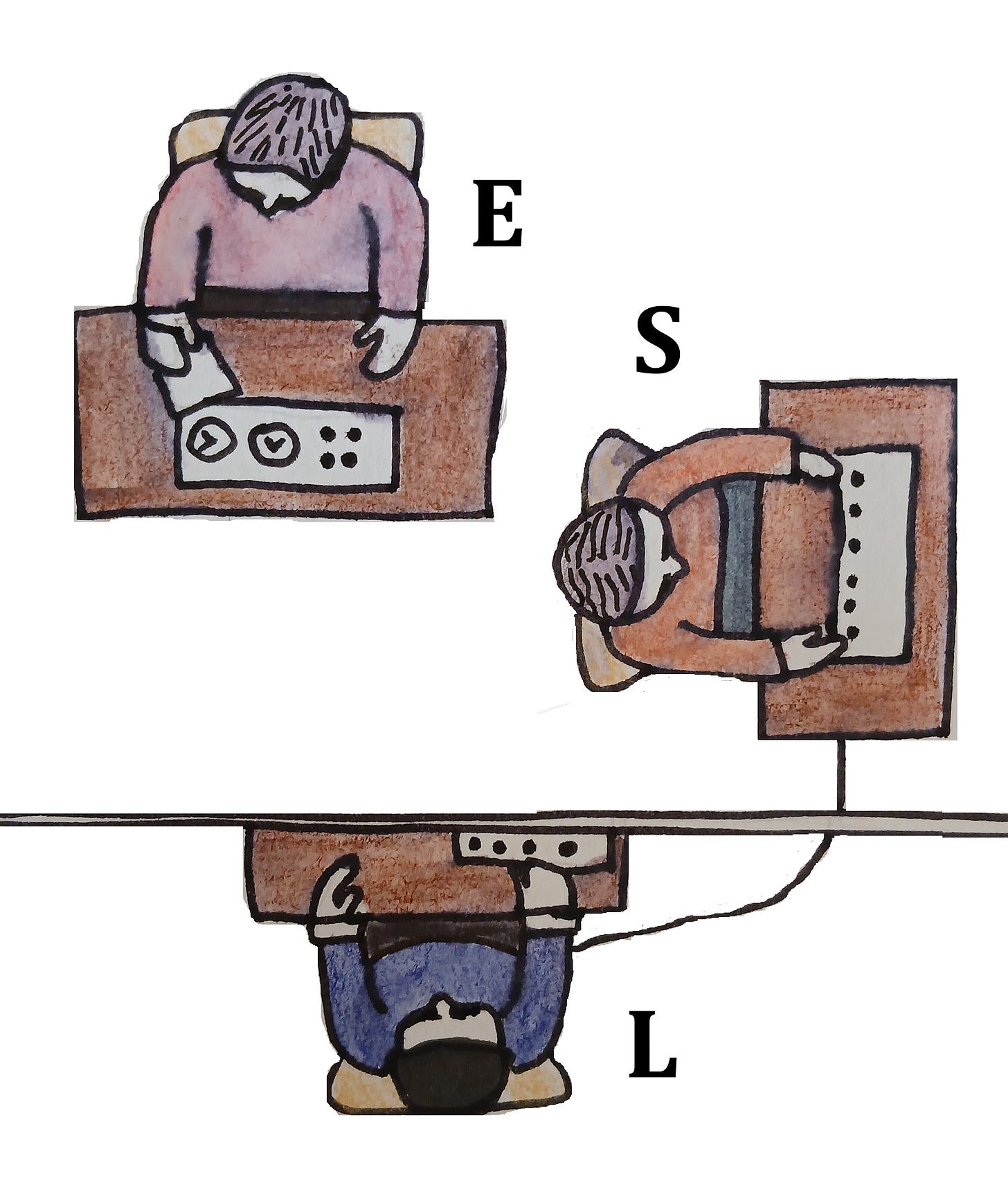

Illustration of the basic test format. E = ‘Experimenter’; S = ‘Subject’ — the genuine test subject in the experiment, also referred to as ‘Teacher’. L = ‘Learner’, a paid actor completing basic memory tests while hooked up to a shock generator.

Stanley Milgram conducted his now-famous experiments from Yale University’s psychology department between 1960 and ‘63. He was haunted by the millions of people systematically slaughtered on command during the Nazi era. Unsatisfied with simply blaming Hitler, or even the Nazis, Milgram wrote: “These inhumane policies may have originated in the mind of a single person, but they could only have been carried out on a massive scale if a very large number of people obeyed orders.” He studied the Nuremberg trials and saw how “the old story of ‘just doing one's duty’ … was heard time and time again in the defense statements of those accused at Nuremberg.”

Milgram decided to put this defense to the test. He designed his famous shock generator experiment to discover “how far the participant will comply with the experimenter’s instructions before refusing to carry out the actions required of him.”

First he invited Yale students to take part in an ostensible “study of memory and learning.” Each respondent arrived at the psychology lab at an allotted time, along with another apparently naïve participant (a paid actor). The student and actor were welcomed by a man in a lab coat referred to as the ‘experimenter’.

The experimenter explained that he was investigating the effects of punishment on learning and memory. The process would be as follows: one respondent would play the part of ‘teacher’, the other ‘learner’. The teacher would read a series of word pairs to the learner, who was required to complete memory tests based on the word pairs, while hooked up to an electric shock generator. Any time the learner gave a wrong answer, the teacher would administer a shock.

Through a rigged but seemingly random selection process, the actor always wound up in the role of learner. He was hooked up to the shock generator while the test subject took the role of teacher. The subject was required to increase the shock voltage with each wrong answer, in thirty increments: the first shock was a ‘mild’ 15-volts. That one was followed by a series of moderate, strong, intense and extreme shocks, right up to a lethal 450-volt shock administered three times.

In those initial studies on students, subjects did not see or hear the person they were ‘shocking’. Milgram and his colleagues hypothesised that the voltage designations on the control panel would be sufficient to cause them to stop following orders. They thought no more than one or two percent of subjects, “a pathological fringe,” would follow orders right to the end of the shock-board and administer a lethal 450-volt shock three times. They were wrong. About 60 percent of subjects did as directed.

Some critics of that study attributed the results to the heavy institutionalisation of subjects. They said elite university students are perhaps beholden to authority to a degree not representative of the general population. Milgram retook the test with participants from all walks of life. The outcome was unchanged.

Milgram went on to complete eighteen formal variations of the study, looking for the precise indicators for obedience. He concluded that the story of “just doing one’s duty” so often used at Nuremberg was not just “a thin alibi concocted for the occasion. Rather, it is a fundamental mode of thinking for a great many people once they are locked into a subordinate position in a structure of authority.” Through empirical research, Milgram essentially discovered what has long been established in yogic science: the aspect of mind called ahamkara or identification. On the outside, it looks like a desire to be a ‘good’, agreeable person. But it is premised on survival: if I satisfy the man in charge, I will be safe and protected. This mechanism is powerful.

At the level of stated opinion, many study participants felt strongly about refraining from hurting a helpless victim. When asked to make a moral judgment on what constitutes appropriate behaviour in the situation of his experiments, subjects would “unfailingly see disobedience as proper. But values are not the only forces at work in an actual, ongoing situation.” Identification trumps values, reason, conscience and choice. Identification with a “man in charge” leads people to forego these capacities and turn them over. From that point, Milgram found, a person’s “moral concern now shifts to a consideration of how well he is living up to the expectations that the authority has of him.”

Test variations (in list form at the end of this essay)

In the first formal variation of Milgram’s experiments, called ‘remote-victim’, the learner was out of sight and earshot of the teacher. His test answers flashed silently on a signal box, but at 300 volts, he pounded his fists in protest. The laboratory walls resounded with the noise. At 315 volts, it ceased. The learner was apparently unresponsive. He stopped submitting answers. The experimenter advised the subject that no answer constituted a wrong answer, so s/he should continue administering shocks. 26 out of 40 subjects proceeded through to the three 450-volt shocks.

In three variations of the test called ‘voice-feedback’, ‘proximity’ and ‘touch-proximity’, Milgram found proximity to the victim to reduce obedience. While only 35 percent of subjects defied the experimenter in the first experiments, the percentage rose to 37.5 percent when the victim yelled to be released, 60 percent in physical proximity, and 70 percent in touch proximity (which required subjects to force the victim’s hand onto a shock-plate).

Not too hopeful. Still, Milgram noted that at most, only one or two subjects “seemed to derive any satisfaction from shocking the learner.”

The bleakest conclusion that could be drawn from these experiments is the ‘Freudian’ theory — that human beings have an instinct for destruction we normally repress. Milgram’s tests provided an opportunity to release the impulse, and subjects took it gladly. Milgram found little evidence to support that theory. Subjects did not experience release and catharsis at the shock-board, but discomfort, “strain” and clear signs of conscience. They would become “agitated” during the experiments, verbalise reluctance, and get up from their chairs. These reactions were “immediate, visceral, and spontaneous.” At the end of the experiment, “obedient subjects heaved sighs of relief, mopped their brows, rubbed their fingers over their eyes, or nervously fumbled cigarettes. Some shook their heads, apparently in regret.” Milgram noted:

If the individual’s submergence in the authority system were total, he would feel no tension as he followed commands, no matter how harsh, for the actions required would be seen only through the meanings imposed by the authority, and would thus be fully acceptable to the subject.

In one variation of his tests, ‘subject free to choose shock level,’ the experimenter did not tell subjects what shock level to administer, and subjects were left to choose. The great majority delivered only the lowest shocks. They did not seem motivated to hurt the victim themselves, but to follow orders.

Milgram wanted to know what would compel subjects to act on their conscience, and defy orders. What if the learner strapped to the chair was especially vulnerable? Milgram had the learner (actor) complain of a heart condition after the experimenter’s briefing — but there was no change to the initial results.

“I must conclude that Arendt’s conception of the banality of evil comes closer to the truth than one might dare imagine,” Milgram lamented.

He inquired into “social contract” theory. The actor, still with a heart condition, include a stipulation before being hooked up to the generator that he would only participate in the experiment on the condition that it would be stopped on his command. The experimenter would agree, but not honour the agreement. Sixteen of 40 subjects still followed the experimenter’s commands, to the end of the shock-board. Milgram concluded that “social contract doctrine is a feeble determinant of behaviour.”

How about removing the element of prestige associated with Milgram’s elegant Yale University laboratory? Milgram shifted the study into a “plain” and functional room in the basement of the same building. It had no impact on results. He took his tests away from Yale entirely, to an office building in a nearby industrial city where tests were conducted under ‘Research Associates of Bridgeport’. 48 percent of subjects delivered the maximum shock at Bridgeport, versus 65 percent in corresponding conditions at Yale:

How are these findings to be interpreted? It is possible that if commands of a potentially harmful or destructive sort are to be perceived as legitimate they must occur within some sort of institutional structure. But it is clear from the study that it need not be a particularly reputable or distinguished institution.

More significant changes occurred when Milgram changed the influence and physical presence of the experimenter. In one test, the experimenter gave instructions via telephone. The number of obedient subjects dropped from 26 in the first condition to 9 over the phone.

Milgram also constructed a test in which the learner doing the memory tests, and not the experimenter, would demand the shocks. The actor would still cry in pain from the shocks, but at 150-volts, the experimenter would declare that the learner’s reactions were unusually severe and call a halt to the study. The learner would object, saying a friend of his had done the test and gone right to the end. It would be an affront to his manliness not to proceed. The learner and experimenter would be equally insistent. Milgram reasoned that if the study participant had some sort of destructive impulse, it would surely try to take advantage of the learner’s insistence. Yet not a single subject complied with the learner in this variation. Every subject stopped administering shocks on the experimenter’s order.

In another variation, the experimenter was “unexpectedly” called out of the room, leaving an accomplice in charge. The accomplice then appeared to have the “idea” of increasing the shock voltage every time the learner made an error in the memory tests. Sixteen out of twenty subjects disobeyed him.

With those sixteen subjects, the experiment continued. The accomplice feigned disgust at their noncompliance and declared that he would just have to administer the shocks himself. Virtually all sixteen subjects protested. Five took physical action against either the accomplice or the shock generator, and one large man lifted the accomplice from his chair, threw him into a corner of the laboratory, and did not allow him to move until he had promised not to deliver further shocks.

Milgram concluded: “Whatever leads to shocking the victim at the highest level cannot be explained by autonomously generated aggression but needs to be explained by the transformation of behaviour that comes about through obedience to orders.” Subjects in the Milgram experiments were not aggressive, vindictive, or hateful. Milgram argued:

Men do become angry; they do act hatefully and explode in rage against others. But not here. Something far more dangerous is revealed: the capacity for man to abandon his humanity, indeed, the inevitability that he does so, as he merges his unique personality into larger institutional structures.

Two interesting test variations confronted study participants with two authority figures — two experimenters — who give different instructions. In one case, when the participant who would have been a ‘learner’ does not show up, the experimenters flip a coin to decide who will sit in the chair, so that the experiment can continue and they can meet their deadline. The experimenter in the chair ends up changing his mind and asking to be released, while the other one tells the study participant to continue. “What occurs is quite striking,” says Milgram, “the experimenter, strapped into the electric chair, fares no better than a victim who is not an authority at all.”

In the other variation with two experimenters, they argue about whether to proceed with the experiment at the 150-volt level, both directing their remarks at the study participant. One instructs the participant to proceed, the other to stop. Not a single subject “took advantage” of the instructions to go on. For all of them, “the disagreement between the authorities completely paralysed action.” Milgram notes, “in other variations nothing the victim did — no pleas, screams, or any other response to the shocks — produced an effect as abrupt and unequivocal.” Identification determines action, and when identification is in crisis, immobilisation occurs. Milgram observed:

An interesting phenomenon emerged in this experiment. Some subjects attempted repeatedly to reconstruct a meaningful hierarchy. Their efforts took the form of trying to ascertain which of the two experimenters was the higher authority. There is a certain discomfort in not knowing who the boss is, and subjects sometimes frantically sought to determine this.

Milgram did not discover a sadistic impulse through his studies, but what in yogic science is called ahamkara (identification). He saw how our identifications ‘trump’ values, conscience, reason and choice, and discovered the human capacity to unconsciously outsource responsibility onto an external agent. He saw how this outsourcing of responsibility allowed people to commit acts that, in other contexts, they would consider immoral and not think themselves capable of.

One particularly obedient participant in Milgram’s experiments was Pasqual. He was among the relatively few subjects who administered 450-volt shocks while being instructed via telephone. He thought he had killed someone. In a follow-up interview, he described his time spent time in the military:

… when I was in the service, [if I was told] ‘You go over the hill, and we’re going to attack,’ we attack. If the lieutenant says, ‘We’re going to go on the firing range, you’re going to crawl on your gut,’ you’re going to crawl on your gut. And if you come across a snake, which I’ve seen a lot of fellows come across, copperheads, and guys were told not to get up, and they got up. And they got killed.

Pasqual was not a psychopath — he had been thoroughly trained to submit his will to authority in the military.

“This is, perhaps, the most fundamental lesson of our study,” Milgram wrote, “ordinary people, simply doing their jobs, and without any particular hostility on their part, can become agents in a terrible destructive process.”

This is a two-part series — next week, we will hear about Milgram’s findings on dissent. We’ll hear from two exceptional Milgram experiment dissenters, and about the test variation that inspired the most non-compliance.

Source: Stanley Milgram, 1974. Obedience to Authority. London: Tavistock.

Study variations:

Remote-victim

Voice-feedback

Proximity

Touch-proximity

A new baseline condition (the basement laboratory)

Change of personnel

Closeness of authority

Women as subjects

The victim’s limited contract

Institutional context (the Bridgeport tests)

Subject free to choose shock level

Learner demands to be shocked

An ordinary man gives orders (accomplice takes charge)

13a. The subject as bystander

Authority as victim: an ordinary man commanding

Two authorities: contradictory commands

Two authorities: one as victim

Two peers rebel

A peer administers shocks

Great piece, Renee — thanks for detailing this for us!