The Milgram experiments: Findings on dissent

What makes people choose conscience over compliance? Milgram explored the question in his 1960s shock generator tests. We previously explored his findings on compliance - now we investigate dissent.

This essay is the second in a two-part series on Stanley Milgram’s famous 1960s shock generator experiments. If you just got here, you may wish to read the first part — it offers an overview of the experiments and key findings. Click here:

Jan Rensaleer, an industrial engineer, was an exceptional test subject in the famous Milgram experiments of 1960-63.

To recap (skip these two paragraphs if you don’t need a quick recap): Stanley Milgram conducted his experiments at Yale University’s psychology department, seeking out subjects for an ostensible “study of memory and learning.” Each respondent arrived at the psychology lab at an allotted time, along with another apparently naïve participant who was really a paid actor.

The student and actor were welcomed by a man in a lab coat we will call the ‘experimenter’. He explained the process: one respondent would play the part of ‘teacher’ and the other ‘learner’. The teacher would read a series of word pairs to the learner, who was required to complete a simple memory test afterward. The learner was hooked up to an electric shock generator. Any time he gave a wrong answer, the teacher was to administer a shock. The shock voltage increased with each wrong answer, all the way up to a lethal 450-volt shock that was to be administered three times.

The findings are sobering. Most study participants obeyed the experimenter’s orders to the end of the shock-board (as detailed in the previous essay).

Rensaleer on responsibility

Rensaleer was an exception. He took part in the ‘voice feedback’ test variation, in which the victim in the electric chair could not be seen, but could be heard yelling and protesting. Compliance rates were high. 62.5 percent of subjects delivered the strongest shocks.

Rensaleer’s protests began after administering a 150-volt shock. He heard the victim complain, turned to the experimenter and asked, “What do I do now?” The experimenter told him to continue. That was a typical subject-experimenter interaction, but at 255 volts, Rensaleer pushed his chair away from the shock generator. He declared: “I can’t continue this way; it’s a voluntary program, if the man doesn’t want to go on with it.”

When subjects resisted, the experimenter followed a script in response. He delivered a series of standard lines until the subject conceded or he either exhausted them all. The first line was, “Please continue.” Since Rensaleer persisted with his protest, he heard all the others, including: “The experiment requires that you go on,” “There is no permanent tissue damage,” and “It is absolutely essential that you continue.” These lines were generally effective. Milgram explained:

Some people treat systems of human origin as if they existed above and beyond any human agent, beyond the control of whim or human feeling. The human element behind agencies and institutions is denied. Thus, when the experimenter says, “The experiment requires that you continue,” the subject feels this to be an imperative that goes beyond any merely human command.

The last of these standard lines was: “You have no other choice.” Rensaleer could not accept that. He replied:

I do have a choice … Why don’t I have a choice? I came here on my own free will. I thought I could help in a research project. But if I have to hurt somebody to do that, or if I was in his place, too, I wouldn’t stay there. I’m very sorry, I think I’ve gone too far already, probably.

When he was later asked who was responsible for shocking the learner against his will, Rensaleer responded: “I would put it on myself entirely.”

Rensaleer was different from many other test subjects in that he did not allow the structure of authority he was acting in to absolve him of responsibility for his actions. That set him apart from the majority. Writing on the study as a whole, Milgram concluded: “The disappearance of a sense of responsibility is the most far-reaching consequence of submission to authority.”

In follow-up interviews, many subjects adopted what Milgram called a “helpless cog” attitude as a moral defence for their actions at the shock-board. They offered some variation of: “If it were up to me, I would not have administered shocks to the learner.” They took the position it was not up to them. Milgram observed, “the person entering an authority system no longer views himself as acting out of his own purposes but rather comes to see himself as an agent for executing the wishes of another person.”

One subject, Fred, protested after administering an 180-volt shock. “I can’t stand it,” he said. “I’m not going to kill that man in there. You hear him hollering?” The experimenter delivered some of his scripted lines. Fred said: “I refuse to take responsibility. He’s in there hollering!” When the experimenter claimed all responsibility, Fred continued administering shocks. He did so even as the learner yelled out about his heart condition. He obeyed the experimenter all the way to the third 450-volt shock.

Responsibility was an important issue to many subjects, but like Fred, many were happy to concede it.

Comparing interviews and test transcripts, Milgram also observed “a marked discrepancy between the subjects’ moral principles and their actual performance in the laboratory.”

‘Two peers rebel’

To clearly identify the factors in compliance and conscience-driven dissent, Milgram did 18 variations of his experiment. He found that proximity to the victim increased the likelihood of noncompliance, especially if the subject had to be physically involved in shocking the victim. If the experimenter was somehow vague — if he was physically absent and gave orders by phone, or if he allowed the subject any choice in the matter — noncompliance rates also rose. But the biggest determiner of dissent was found in the test variation called ‘two peers rebel’.

‘Two peers rebel’ was designed to allow Milgram to find out to what degree “group influence can release the subject from authoritarian control and allow him to act in a direction congruent with his values and personal standards.”

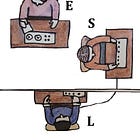

The basic experiment was the same, but there were three ‘teachers’ positioned by the shock generator instead of one (there was still just one ‘learner’ in the electric chair). All these participants were actors, except the sole naïve study participant in the role of Teacher 3. Teacher 1 read the word pairs aloud to the learner, and Teacher 2 determined whether the answer was correct. Teacher 3, the test subject, administered a shock for each wrong answer, increasing the voltage each time.

At 150-volts, the learner protested. Teacher 1 told the experimenter he did not wish to continue. The experimenter insisted he must, but Teacher 1 got up from his chair and took a seat in another part of the room. The experimenter tried and failed to bring Teacher 1 back. He would then give up and tell the other two ‘teachers’ to continue.

At 210 volts, Teacher 2 also refused to participate further. He moved away from the shock-board, saying, “I’m willing to answer any of your questions, but I’m not willing to shock that man against his will. I’ll have no part of it.”

The fate of the experiment now lay with Teacher 3, the test subject. The experimenter told Teacher 3 that it is essential the study be completed. 36 out of 40 subjects defied the experimenter. Milgram observed:

The effects of peer rebellion are very impressive in undercutting the experimenter’s authority. Indeed, of the scores of experimental variations completed in this study, none was so effective in undercutting the experimenter’s authority as the manipulation reported here.

The test also includes a warning for activists with initiative, those who act first: purge yourself of the desire for recognition or credit. In follow-up interviews, study participants did not tend to talk about themselves as having been influenced by their peers. “A majority of defiant subjects … denied that the confederates’ action was the critical factor in their own defiance,” Milgram found. They would say things like, “Well, I was already thinking about quitting when the guy broke off.” It makes me think about the amount of people these days who accuse one another of being on the “wrong side of history”. I see that phrase as indicative of someone who is motivated by posterity. Posterity as a motivation will not take you very far, because it will leave you seeking credit that may not be forthcoming.

The ultimate authority

Another dissenter was an Old Testament professor. He partook in the ‘proximity’ experiment, in which subjects were seated near to learners. After being seated, the professor immediately adjusted his seat to look more squarely at the learner — and while administering shocks, he drew his lips back to bare his teeth in discomfort. He refused to continue past 150 volts. The transcript is as follows:

Experimenter (E): It’s absolutely essential to the experiment that we continue.

Professor (P): I understand that statement, but I don’t understand why the experiment is placed above this person’s life.

E: There is no permanent tissue damage.

P: Well, that’s your opinion. If he doesn’t want to continue, I’m taking orders from him.

In a follow-up interview, the professor was asked: “What in your opinion is the most effective way of strengthening resistance to inhumane authority?” He answered: “If one had as one’s ultimate authority God, then it trivialises human authority.”

In his book on the tests, Obedience to Authority (1974), Milgram’s response to this answer seems to convey disappointment. He says the professor did “not disobey so much as [he] shifts the person from whom he will take orders.” But this assumes that real dissent can only happen without recourse to any authority, without identification with anyone or anything at all.

Yogic science, which is echoed in Milgram’s findings, takes a different perspective on this. The word yoga means ‘to yoke’, and one meaning of this relates to identification. Yoga does not ask us to try to amputate or transcend the mechanism of identification, but to consciously bind it to a life-affirming source. In the Hindu Bhagavad Gita, one of the most important yogic texts, Krishna (an avatar of God) guides the book’s troubled protagonist, Arjuna, to use the powerful binding force of identification to ‘yoke’ himself and his actions to God. According to Krishna, this is how Arjuna will gain the clarity and strength to proceed through his crisis situation with integrity.

“I don’t understand why the experiment is placed above this person’s life,” is what the professor said to the experimenter. His ultimate identification was with life, which he also called God, and which he saw in the learner. His actions followed those identifications, and with them he taught the rest of us a lesson, just like Jan Rensaleer and the subjects in the ‘two peers rebel’ variation.

Proximity to victims and distance from authority figures make people more likely to act on conscience rather than command. But when a person considers her/himself 100% responsible for her/his own actions, and for the choice of which authority to follow, they are more likely to act on conscience even when the conditions are not conducive. Such people put themselves at risk — but they also inspire. The Milgram experiments showed that nothing inspires dissent more than self-possessed individuals acting on conscience, signaling to others that they can do the same.

In the next post we will continue on the theme of identification. Violence expert Gavin de Becker helps readers to reclaim their minds and intuition from the distorting influence of identification in his book, The Gift of Fear: Survival Signals that Protect Us from Violence (1997). We will review his suggestions. Stay tuned!

Have heard about that study before but not in such detail, thanks! Reminded of a book about drone 'pilots', "Hellfire from Paradise Ranch: On the Front Lines of Drone Warfare" by Joseba Zulaika

Brilliant piece.